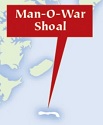

Seeking to counter a shortage of oyster habitat in the Chesapeake Bay, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources is renewing a controversial bid to dredge old shells that have built up over centuries from an ancient reef southeast of Baltimore. Reviving a plan abandoned in 2009, the DNR has applied to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for a permit to take 5 million bushels of shells from Man-O-War shoal just beyond the mouth of the Patapsco River. Ultimately, though, the state wants to barge away 30 million bushels, or about a third of the 456-acre reef.

Seeking to counter a shortage of oyster habitat in the Chesapeake Bay, the Maryland Department of Natural Resources is renewing a controversial bid to dredge old shells that have built up over centuries from an ancient reef southeast of Baltimore. Reviving a plan abandoned in 2009, the DNR has applied to the U.S. Army Corps of Engineers for a permit to take 5 million bushels of shells from Man-O-War shoal just beyond the mouth of the Patapsco River. Ultimately, though, the state wants to barge away 30 million bushels, or about a third of the 456-acre reef.

The shells are needed t o replace or augment oyster reefs worn down by harvesting and buried under an accumulation of silt, the DNR said. State officials said they would use much of the dredged shell in future large-scale, restoration projects. Some would also go to help the public fishery, though, and to assist oyster farmers growing bivalves on leased plots of the Bay and its tributaries.

But the DNR’s request is drawing flak from conservationists, fishermen and even some watermen who might benefit.

Dozens of angry residents crowded into Sparrows Point High School on a February night to beg the Corps not to allow dredging on one of Baltimore County’s last great fishing spots. The shoal is a trove for anglers and boaters in large part because the roughly 100 million bushels of shell underneath the water there provide a prime feeding ground for a variety of fish, including striped bass. The Corps also scheduled a meeting in Cambridge that was more sparsely attended. There, about a dozen people spoke, more than half in favor of the project.

“It would be a crime to just destroy this bar,” said Frank Holden, president of the Maryland Saltwater Sportfishing Association after the two-hour hearing at Sparrows Point. “It’s the last one, and it’s really quality fishing.”

About three dozen of the 150 people attending the Sparrows Point hearing spoke against the dredging. The lone voice for it was Sarah D. Sheppard, speaking on behalf of the Clean Chesapeake Coalition. Sheppard is an attorney with the law firm Funk and Bolton, which represents the coalition. The Clean Chesapeake Coalition has been opposed to reef restoration projects using alternatives to oyster shell. Sheppard derided the state’s one-time use of fossilized shell as “Florida slurry” because it initially came from a quarry in the Sunshine State. Sheppard said Maryland natural resources officials have been “dumping unwashed and untested” substrate into the Bay for young oysters to settle on, and she contended that it would be better to use real oyster shells instead.

DNR officials have long agreed that oyster shells are the best substrate for growing new bivalves, whether for aquaculture, harvest or restoration. But for the past decade, oyster shell has been expensive and difficult to obtain, as many states with oyster fisheries are keeping shells for their own projects. That has forced both the state to turn to alternative sources, such as Florida fossil shell and, more recently, clam shells from New Jersey. Both have been used in large-scale restoration projects in three tributaries of the Choptank River — Harris Creek, the Little Choptank River and Tred Avon River. The work is unfinished in two of those waterways, but scientists say the alternatives have proven suitable for young oysters, or spat. Several watermen succeeded in getting the Tred Avon reef construction halted, at least temporarily, in part because they objected to the types of substrate used.

Robert T. Brown Sr., president of the Maryland Watermen’s Association, said his group opposes the Man-O-War Shoal dredging, though he said some individual watermen might favor it.

“That’s the only oyster bar Baltimore County has,” he said.

“We need to rebuild the upper part of the Bay in case MSX and Dermo come in,” Brown added, referring to the two parasitic oyster diseases that devastated the Bay’s bivalve population in the 1960s and again in the 1980s and ‘90s.

The watermen’s group president said he is also concerned about how the dredged shells would be apportioned between sanctuaries, which are off-limits to harvesting, and areas that remain in the public fishery. David Goshorn, an assistant DNR secretary, acknowledged that the split was still to be determined. The DNR printed material in the school lobby for the hearing outlined three scenarios: 90 percent aquaculture or sanctuaries and 10 percent harvest; 75 percent harvest and 25 percent aquaculture and sanctuaries; or 50 percent on each.

The DNR’s earlier plan to dredge at Man-O-War Shoal proposed to set aside 90 percent of the shell for sanctuaries and 10 percent for harvest. The Chesapeake Bay Foundation supported that version, but the Annapolis-based environmental group does not back this plan because there’s “too much ambiguity,” according to Doug Myers, CBF’s Maryland scientist.

The last time the department dredged the shoal was 2006. Recreational anglers, led by conservationist and physician Kenneth Lewis, let the department know it would oppose any more dredging. When the department declined to pursue another permit, the General Assembly twice passed bills requiring the DNR to apply again.

DNR officials say they have amended their dredging plan with the hope that it will be more palatable to recreational anglers. It now proposes a five-year experimental permit that will take only 5 percent of what is on the shoal, while studying the impacts before and after the initial dredging of about 2 million bushels. This conservative approach, Goshorn told the Sparrows Point crowd, will protect the reef and the Chesapeake’s oyster.

“Oysters are in dire straits in the Chesapeake Bay. We are spending a lot of resources to restore them,” he said. “They need bottom, and the best bottom is shell.”

It will likely be months before the Corps makes a decision on the permit, said agency spokeswoman Sarah Gross. The Corps will first write to the DNR with a summary of the comments raised during the comment period, which ended Feb. 18, and identify the ones DNR must address. It may also seek new information.