A fishing tournament in the Chesapeake Bay recently highlighted finding a diversity of species—rather than catching the biggest fish—as its defining element. Where best to find many kinds of fish? The Chesapeake Bay Foundation, organizer of the Rod and Reef Slam Fishing Tournament, defined restored oyster reefs as the target area for their second-annual event. This enabled organizers to highlight how vibrant these areas are—and to collect data on the kinds of fish that now frequent these restored reefs.

In all, 28 anglers in powerboat, kayak, and youth categories participated in the event; they logged nearly 80 catches. This was nearly double the field from the inaugural event, showing that recreational fishermen in the area are keen to wet a line in these restored areas.

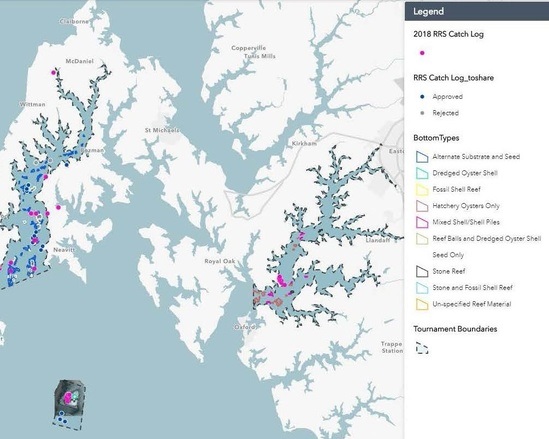

It was a catch, photograph, and release tournament; anglers entered photos and data about their catches into the iAngler Tournament app to document their successes. At the tournament party, participants checked out a map that included data provided by the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office describing what kinds of reefs they caught their fish near—existing natural oyster reefs, restored reefs built out of shell and seeded with baby oysters, or simply areas that had been given a jump-start by being seeded with baby oysters.

In all, 13 species—such as striped bass, oyster toadfish, white perch, blue crab, croaker, and spot—were caught in the six restoration areas included in the tournament. Areas in Harris Creek and the Tred Avon and Little Choptank rivers on Maryland’s Eastern Shore the anglers used are oyster sanctuaries where NOAA and partners are accomplishing large-scale oyster restoration toward the Chesapeake Bay Program’s goal of restoring native oysters to 10 Bay tributaries by 2025.

To support these efforts, the NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office provides needed science through sonar surveys and habitat analysis work both before (to site projects) and after (to monitor progress) reef restoration takes place.

Organizations with unique capabilities partner to accomplish large-scale oyster restoration in Maryland. Together, since 2011, these partners have restored more than 670 acres of oyster reef habitat total in Harris Creek and the Tred Avon and Little Choptank rivers—that’s nearly 4 billion baby oysters.

In addition to the science NOAA provides, NOAA works with the Maryland Department of Natural Resources, which has jurisdiction in these waters; U.S. Army Corps of Engineers, which physically constructs reefs; and the nonprofit Oyster Recovery Partnership, which uses its purpose-designed vessel to plant baby oysters in designated areas. The University of Maryland Center for Environmental Science’s hatchery provides the baby oysters—funded by NOAA and others. Related efforts and additional partnerships are supporting large-scale restoration in Virginia.

Other efforts to support restoration are in progress as well. For example, the Chesapeake Bay Foundation works with communities around the Chesapeake Bay to restore oyster reef habitat areas, including using reef balls to create reef structure. They also run an “oyster gardening” program through which participants care for spat on shell oysters in cages until they are large enough to be safely moved to sanctuary reefs.

Restoration efforts in the Chesapeake Bay are under way because oyster populations are estimated to be at only 1-2% of their historic levels. Oysters filter water, and the reefs they form provide needed habitat for fish, crabs, and other species. The NOAA Chesapeake Bay Office’s Oyster Reef Ecosystem Services project is working to quantify the benefits that oysters and oyster reefs bring to the Bay ecosystem.

For anglers, a key benefit is that oyster reefs are great places for fishing!